Guidelines for the Production and Use of Biochar in Organic Farming

by Biochar Science Network

Version 2.4

Please pay attention that this is a working paper and that different versions may circulate. Please verify to use the latest version. Correction of an earlier version is marked red.

Introduction

Biochar is carbon produced through pyrolysis for use in agriculture. For biochars that do not meet the minimum standard set for agricultural purposes, the generic term pyrochar should be used.

Pyrochar refers to all coal, produced through pyrolysis of biomass. Biomass pyrolysis applies to the thermochemical decomposition of organic matter under anaerobic conditions at temperatures of 350 to 900 ° C. Torrefaction, hydrothermal carbonisation, coking and combustion are further charring processes whose end products cannot be described as pyrochar.

Biochars are therefore special pyrochar which are characterised by additional environmentally sustainable production, quality and conditions of use and are certified. The following criteria related to the feedstock used, the method of pyrolysis, the properties of the biochar and the application of biochar should be met for the use of biochar in organic farming.

A. Feedstocks

1. Pure organic waste materials without relevant toxic pollution by heavy metals, paint, solvents, etc. Clean separation of non-organic wastes such as electronic waste, plastics, rubber, etc. must be assured.[In an appendix, a whitelist with suitable biomass feedstocks will be added: tree and grass clippings, bark, sawdust, fermentation residues, organic household waste, sewage sludge, manure, food waste, animal waste ...]

2. Agricultural and forestry residues such as husks, fruit peels, fruit seeds, pulp, bark, etc. [whitelist]

3. Agricultural products from cultivation of energy crops which are produced without synthetic pesticides, herbicides, mineral fertilisers and genetically modified seeds. The means of producing biomass for carbon sequestration and energy production has to favour the biodiversity and the stability of the agro-ecosystem.

4. The cultivated surface for energy crops should not exceed 15% of all agricultural land in a region. [this 15% threshold should limit competition with food production, the exact percentage is to be discussed]

5. Biochar may only be obtained from forest wood if the sustainable management of the forest is assured (PEFC, FSC). In particular, deforestation of rain forests, as is currently done for the production of charcoal in wide areas of the world, must be prevented.

6. The maximum distance for transport of the feedstock for biochar production should not exceed 80 km.

B. Pyrolysis

1. The pyrolysis of biomass must occur as an energy-autonomous process. The energy used to operate the plant (electricity for propulsion, ventilation and BMSR) must not exceed 10 % of the calorific value of the biomass being pyrolysed. [The exact percentage is to be discussed. The important thing is to have a limit to ensure that fossil fuels are not used to heat the reactor (beyond start-up) and that unused hot exhaust gases do not simply escape into the atmosphere (as in traditional charcoal kilns).]

2. The syngases produced during pyrolysis must be captured and not be allowed to escape into the atmosphere.

3. Combustion of syngases must comply with prevailing emission limits for wood-burning. The following emission limits should be respected: (based on 11 Vol.-% O2): CO: 250 mg/m3; dust: 50 mg/m3; NOx: 500 mg/m3; total-C: 50 mg/m3; HCl: 30 mg/m3; SOx: 350 mg/m3.

4. The sustainable use of waste heat resulting from the combustion of syngases must be guaranteed. Energy loss through heat must not exceed 5o % of the calorific value of the pyrolysed biomass.

In order to meet the requirements listed in B, each production plant must be approved and certified.

C. Characteristics of Biochar

1. Nutrient content levels must adhere to fertiliser regulations [The variations in the nutrient content of different biochars are very high (between 170 g/kg and 905 g/kg). According to most fertiliser regulations, soil nutrient levels must be determined in any case. The identified nutrient content levels establish the maximum allowable amounts for soil incubation. But absolute nutrient content is not as relevant as nutrient availability, which is difficult to determine (e.g. nutrient availability of phosphorus is around 15%, that of nitrogen is sometimes under 1%). According to prevailing fertiliser regulations, however, only the absolute values are considered (and despite many years of discussion still only the absolute values are accepted in most compost ordinances). The limits set by the soil regulations are well below the relevant nutrient availability values for biochar and are therefore sufficient as an exclusion criterion.]

2. Carbon content >50% [The carbon content of pyrochar varies between 25 and 95% depending on the biomass and process temperature. (For example: chicken manure has 26%, beech 86%). In very mineral-rich biomasses such as sewage sludge or animal manure, the ash content is predominant in the pyrolysis product. Correspondingly, these products fall under the category of ashes with a more or less high content of biochar. In order to achieve the most efficient nutrient flow, these mineral-rich biomasses should rather be composted or fermented thereby making nutrients easier available to plants. The specification of the C content is particularly relevant for the generation of CO2 certificates.]

3. Molar H/C ratio <0.6 and >0.1 [The charring temperature and thus the stability of the biochar can be derived from the molar H/C ratio. This ratio is among the most important characterisation criteria for biochar. The values vary depending on the biomass feedstock and production procedures. Values outside the above-mentioned range are suggestive of inferior coal and inadequate pyrolytic process.]

4. Heavy metal content adheres to the standard guidelines of the prevailing Compost Ordinance [As with composting, almost the entire quantity of heavy metals from the feedstock biomass is retained in the biochar, with the final substrate being more concentrated. Unlike in the case of compost, heavy metals are readily fixed by biochar and are blocked for the long term. Presently, how durable this blockage is cannot be determined with certainty. Since biochar, unlike compost, is introduced only once into the soil (or several times up to a maximum final concentration), toxic accumulation of heavy metals is unlikely to take place. Nevertheless, it is politically improbable to allow higher heavy metal content levels for biochar than for compost. At the very least it would entail a lengthy road through public bureaucracies. However, there is no reason not to comply with the prescribed limits set by the Compost Ordinance for heavy metals. For the more polluted pyrochar sufficient other applications exist.]

5. PAH Contents < 4 mg EPA 16 PAH/kg DM, PCB content <0,2 mg/kg DM [This value corresponds to the Compost Ordinance. However, biochar binds PAH efficiently, and allows bacteria to degrade them at least partly. Hence, the PAH-risk is relatively low. Nevertheless, for the time being no higher PAH and PCB levels than those for compost should be allowed. Due to the high absorption capacity of biochar, the most standard methods to analyse PAH are not valid for biochar. Results are often less than 10% of the real values. A more exact method for analysing PAH in biochar will be proposed by the BCSN in the beginning of 2011]

6. Furans < 20 ng/kg DM (I-TEQ OMS);

7. Polyaromatic carbon (black carbon) content. [Low polyaromatic carbon levels suggest non-pyrolytically produced coals such as hydrochars. Excessively high levels are an indication of pyrolysis temperatures above 900°C signifying coking of coal. Through coking, however, biochar loses its characteristics and can be no longer be recommended for agricultural use. It is still not possible to give an absolute percentage value with the present state of knowledge because the values vary widely depending on method of analysis. A standard of method and their validity on the basis of the different biochars and substrates have to be agreed on. Since the usual methods are also very expensive, the value despite its high theoretical significance is probably not relevant as a practical standard value for the present guidelines.]

8. pH levels - [The pH values fluctuate between 6 and 10 and are not critical for denial of certification. However, they have to be specified, since a shift in the soil pH value has an enormous influence on soils.]

9. Bulk density [The density may vary between 100-1000 g/l depending on biomass and maximum pyrolytic temperature. It is therefore not an exclusion criterion. The density is easily determined and is an indicator of the pore volume. It should therefore be reported in order to characterise the biochar.]

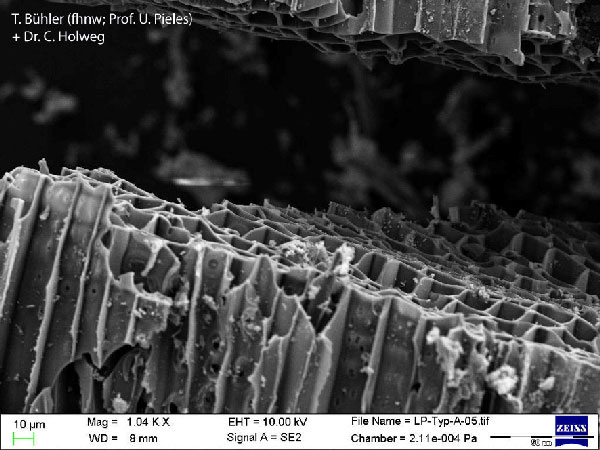

10. Specific surface area and pore volume [Two central values for the characterisation of biochar. Both values depend both on the pyrolysed biomass and the pyrolysis process used (especially maximum temperature, residence time, particle size). The determination of both values is not yet methodologically standardised. The values vary greatly depending on the method used. No exclusion criteria based on these two values can be given thus far.]

For points 5 and 6, each facility should be inspected regularly, since not every batch can be checked due to the high costs of analysis. All other points must be checked once for identical feedstocks and processes.

D. Application of Biochar

1. Application into the soil should only be done in combination with organic carbon (compost, humus-rich soil, Bokashi compost, molasses, manure, etc).

2. Application should only be on permanently vegetated soils or grounds with permanent green or mulch cover. Otherwise biochar will be degraded via erosion and could partly spread as aerosols in the air.

3. Minimal tillage, since otherwise loss of humus and biochar and consequent decreased attainment of the desired carbon sink levels will result.

4. If application into the soil does not take place in conjunction with dust-preventive binding materials such as moist compost, soil, Bokashi, etc., a granule size of > 5 mm or the use of an efficient dust fixing fluid must be ensured. The same has to be observed for transportation and decharging.

Point D is to be controlled through farmers, points A - C by the manufacturer.

The present guidelines are a first draft. Amendatory propositions and critics are welcome and will be integrated into the following consultations. Please check always the number of version when citing these guidelines. The actual version is 2.3

Contact: Delinat Institute for Ecology and Climate Farming, www.delinat-institut.org, info@delinat-institut.org1. Pure organic waste materials without relevant toxic pollution by heavy metals, paint, solvents, etc. Clean separation of non-organic wastes such as electronic waste, plastics, rubber, etc. [In an appendix, a whitelist with suitable biomass feedstocks will be added: tree and grass clippings, bark, sawdust, fermentation residues, organic household waste, sewage sludge, manure, food waste, animal waste ...]

2. Agricultural and forestry residues such as husks, fruit peels, fruit seeds, pulp, bark, etc. (whitelist)

3. Agricultural products from cultivation of energy crops which are produced without synthetic pesticides, herbicides, mineral fertilisers and genetically modified seeds. The production of biomass for carbon sequestration and energy production has to be done in a way that preserves the biodiversity and stability of the agro-ecosystem.

4. The cultivated surface for energy crops should not exceed 15% of all agricultural land in a region. [this 15% threshold should limit competition with food production, the exact percentage is to be discussed]

5. Biochar may only be obtained from forest wood if the sustainable management of the forest is assured (FSC-standard). In particular, deforestation of rain forests, as is currently done for the production of charcoal in wide areas of the world must be prevented.

6. The maximum distance for transport of the feedstock for biochar production should not exceed 80 km.

FVA-WÖ

2010-11-21 20:42

Die Verwendung von Biokohle erscheint mir sowohl hinsichtlich Erhaltung/Verbesserung der Bodenfruchtbarkeit als auch hinsichtlich C-Bindung ein vielversprechender Weg. Was ich absolut nicht verstehe, ist dass im vorliegenden Artikel vergessen wird auf die PEFC-Zertifizierung als wichtigstes weltweites Zertifizierungsverfahren für Holz hinzuweisen. Der alleinige Verweis auf FSC führt wegen der geringen Verbreitung dazu, dass Holz eher aus Plantagen kommt als aus europäischer nachhaltiger Forstwirtschaft.

hps

2010-11-21 21:13

Vielen Dank für den Hinweis, wir werden dies entsprechend aufnehmen. Das in Klammern gesetzte FSC war als eine von mehreren möglichen Zertifikaten gedacht. In Entwicklungsländern, wo die meisten Wälder keiner Zertifizierung unterliegen, müsste eine pragmatische Lösung gefunden werden, die eine nachhaltige Waldbewirtschaftung gewährleisten. Aber es wird ohnehin nicht möglich sein, eine weltweite Richtlinien für Biokohle aufzustellen. Insofern ist das vorliegende Papier vor allem ein Vorschlag für die Schweiz und die EU, auf dessen Grundlage dann verschiedene nationale oder regionale Richtlinien adaptiert werden können.

Gerald Dunst

2010-11-30 13:03

Ich habe Bedenken, dass die Forderung, Biokohle nur aus Rohstoffen herzustellen, die selbst "Bio" sind, etwas zu weit geht und sich die Biolandwirtschaft dadurch selbst schadet!

Fachlich gesehen ist Elefantengras von einem konventionellen Betrieb einem "Bio-Elefantengras" für die Verkohlung sicher gleichwertig. Man hat beispielsweise auch in der Kompostverordnung einen sinnvollen Kompromiss gefunden, wo getrennt gesammelte Küchenabfälle generell als Rohstoff für Komposte im Biolandbau zugelassen worden sind. Ich meine, dass man sich vielmehr auf das Endprodukt "Biokohle", und weniger auf die Ausgangsstoffe konzentrieren sollte. Es könnte sonst nämlich passieren, dass die Biokohle für die Masse der Biobauern nicht finanzierbar wäre und in erster Linie die Böden der konventionellen Betriebe saniert werden könnten.

Weiters bin ich der Meinung, dass es für eine detailierte Regelung ohnedies noch zu früh ist - es gibt viel zu wenige Erfahrungen im Bereich der Anwendung. In dieser ersten Versuchsphase sollte es ausreichen, dass die Schadstofffreiheit der Biokohle nachgewiesen wird. Ein "Wildwuchs" ist aufgrund des hohen Marktpreises zur Zeit ohnehin nicht zu befürchten.

hps

2010-11-30 13:11

Die Punkte A2 und A3 regeln lediglich die Biomassen, die aus unmittelbar zur Biomasse-Produktion angelegten Flächen gewonnen werden. Für diese Flächen wurde biologischer Anbau gefordert, um nicht auf der einen Seite Humusaufbau und Klimafarming zu betreiben und auf der anderen Seite Landflächen durch intensive Landwirtschaft zu zerstören.

Für Punkt A1 hingegen, der den Einsatz von organischen Reststoffe betrifft - egal ob landwirtschaftliche, forstwirtschaftliche oder sonstige organische Abfälle - gilt die Einschränkung, dass sie aus biologischem Anbau stammen müssen nicht.